Pandas from Numpy#

This tutorial will show the fundamental structure of Pandas Data Frames. We will look at the components that constitute a Data Frame - for instance, Numpy arrays - in order to gain a deeper understanding of the raw ingredients that more advanced Pandas methods and functions operate on.

What is Pandas?#

Pandas is an open-source python library for data manipulation and analysis.

Note

Why is Pandas called Pandas?

The “Pandas” name is short for “panel data”. The library was named after the type of econometrics panel data that it was designed to analyse. Panel data are longitudinal data where the same observational units (e.g. countries) are observed over multiple instances across time.

The Pandas Data Frame is the most important feature of the Pandas library. Data Frames, as the name suggests, contain not only the data for an analysis, but a toolkit of methods for cleaning, plotting and interacting with the data in flexible ways. For more information about Pandas see this page.

The standard way to make a new Data Frame is to ask Pandas to read a data file

(like a .csv file) into a Data Frame. Before we do that however, we will

build our own Data Frame from scratch, beginning with the fundamental building

block for Data Frames: Numpy arrays.

# Import the libraries needed for this page

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

Numpy arrays#

Let’s say we have some data that applies to a set of countries, and we have some countries in mind:

country_names_array = np.array(['Australia', 'Brazil', 'Canada',

'China', 'Germany', 'Spain',

'France', 'United Kingdom', 'India',

'Italy', 'Japan', 'South Korea',

'Mexico', 'Russia', 'United States'])

country_names_array

array(['Australia', 'Brazil', 'Canada', 'China', 'Germany', 'Spain',

'France', 'United Kingdom', 'India', 'Italy', 'Japan',

'South Korea', 'Mexico', 'Russia', 'United States'], dtype='<U14')

For compactness, we’ll also want to use the corresponding standard three-letter code for each country, like so:

country_codes_array = np.array(['AUS', 'BRA', 'CAN',

'CHN', 'DEU', 'ESP',

'FRA', 'GBR', 'IND',

'ITA', 'JPN', 'KOR',

'MEX', 'RUS', 'USA'])

country_codes_array

array(['AUS', 'BRA', 'CAN', 'CHN', 'DEU', 'ESP', 'FRA', 'GBR', 'IND',

'ITA', 'JPN', 'KOR', 'MEX', 'RUS', 'USA'], dtype='<U3')

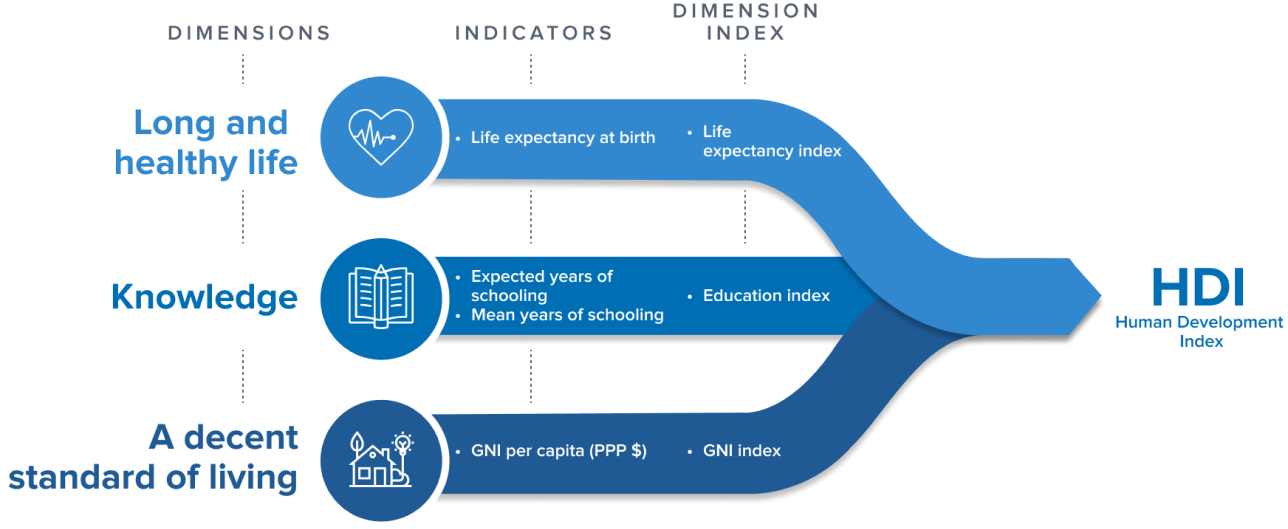

For each of these countries, we have a Human Development Index (HDI) score. The HDI score for a country is a summary over multiple dimensions of human development: life expectancy, average years of schooling and Gross National Income per capita.

# Human Development Index Scores for each country

hdis_array = np.array([0.896, 0.668, 0.89,

0.586, 0.89, 0.828,

0.844, 0.863, 0.49,

0.842, 0.883, 0.824,

0.709, 0.733, 0.894])

hdis_array

array([0.896, 0.668, 0.89 , 0.586, 0.89 , 0.828, 0.844, 0.863, 0.49 ,

0.842, 0.883, 0.824, 0.709, 0.733, 0.894])

By the way, these data are real; they come from statistics compiled by the United Nations. For simplicity, we are only looking at data from the year 2000. See the datasets and licenses page for more detail.

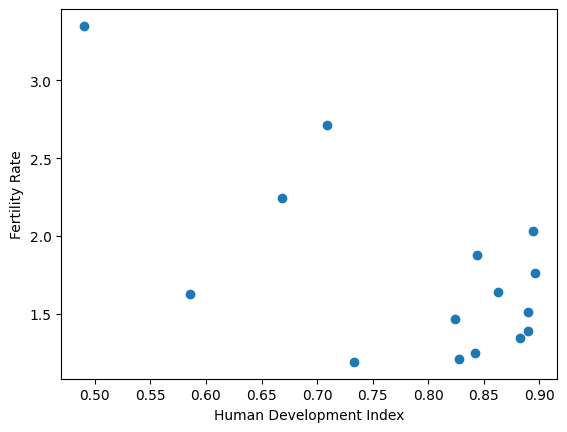

Let’s say we also have the fertility rate for each country. The fertility rate is the average number of children born to to each woman. In due course, we’re interested to see whether HDI can predict the fertility rate values.

# Fertility rate scores for each country

fert_rates_array = np.array([1.764, 2.247, 1.51,

1.628, 1.386, 1.21,

1.876, 1.641, 3.35,

1.249, 1.346, 1.467,

2.714, 1.19 , 2.03 ])

fert_rates_array

array([1.764, 2.247, 1.51 , 1.628, 1.386, 1.21 , 1.876, 1.641, 3.35 ,

1.249, 1.346, 1.467, 2.714, 1.19 , 2.03 ])

As experienced data analysts, we first want to inspect this relationship graphically, for example with the Matplotlib library. Later, we will see that Pandas offers us some streamlined ways of plotting data, without the need to import other libraries.

# Some basic plotting with Matplotlib.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

plt.scatter(hdis_array, fert_rates_array)

plt.xlabel('Human Development Index')

plt.ylabel('Fertility Rate');

Pandas Series (aka an array + an index)#

(Aka is an abbreviation for “Also Known As”.)

We want a good way to keep it clear which value corresponds to each country. We’re going to start with the HDI values.

One way of doing that is to make a new data structure that contains the HDI values, but also has labels for each value. Pandas has an object for that, called a Series. You can construct a Series by passing the values and the labels:

# Make a Series from the `hdis_array`

hdi_series = pd.Series(hdis_array, index=country_codes_array)

hdi_series

AUS 0.896

BRA 0.668

CAN 0.890

CHN 0.586

DEU 0.890

ESP 0.828

FRA 0.844

GBR 0.863

IND 0.490

ITA 0.842

JPN 0.883

KOR 0.824

MEX 0.709

RUS 0.733

USA 0.894

dtype: float64

Notice the index= named argument. Pandas calls the collection of labels for

each value - the Index. Think of the Index as you would an index for

a book. As the index in a book gives you the page number corresponding to

particular word, the Pandas Index of a Series is a way of finding the element

(value) corresponding to a particular country code.

We can get to the collection of labels with

the .index attribute of the Series.

# Show the index of `hdi_series`

hdi_series.index

Index(['AUS', 'BRA', 'CAN', 'CHN', 'DEU', 'ESP', 'FRA', 'GBR', 'IND', 'ITA',

'JPN', 'KOR', 'MEX', 'RUS', 'USA'],

dtype='str')

hdi_series also contains the HDI values, accessible with the .values

attribute:

# Show the values (data) in `hdi_series`

hdi_series.values

array([0.896, 0.668, 0.89 , 0.586, 0.89 , 0.828, 0.844, 0.863, 0.49 ,

0.842, 0.883, 0.824, 0.709, 0.733, 0.894])

Think of the Series as an object that associates an array of values

(.values) with the corresponding labels for each value (.index).

We can access values from their corresponding label, by using the .loc

accessor, an attribute of the Series object.

# Using label based indexing to view a specific value.

hdi_series.loc['MEX']

np.float64(0.709)

.loc is an accessor that allows us to pass labels (that are present in the

.index), and that returns the corresponding value(s). Here we ask for more

than one value, by passing in a list of labels:

# Using label based indexing to view two specific values.

hdi_series.loc[['KOR', 'USA']]

KOR 0.824

USA 0.894

dtype: float64

Notice above, that passing one label to .loc returns the value, but passing

two or more labels to .loc returns a subset of the Series. Put another

way, one label gives a value, but more than one label gives a Series.

Indexing with .loc is called label-based indexing. You can also index by

position, as you would with a Numpy array. Let’s remind ourselves of basic

indexing in Numpy; to get the thirteenth value in the Numpy array of HDI

values, one could run:

# Using integer-based indexing to retrieve a specific value from an *array*.

hdis_array[12]

np.float64(0.709)

Numpy indexing with integers, like the above, is always indexing by position. We count from 0, so position 12 contains the thirteenth element.

You can do the same type of indexing with a Pandas series, with the .iloc

accessor. Think of .iloc as integer indexing, or, if you like, locating

with integers.

# Get the 13th element with `iloc` indexing.

hdi_series.iloc[12]

np.float64(0.709)

# Get the 12th and 15th element with `.iloc` indexing.

hdi_series.iloc[[11, 14]]

KOR 0.824

USA 0.894

dtype: float64

Notice again that one integer to .iloc gives a value, but two or more

integers gives a Series.

You can already imagine that this kind of label-based indexing could be useful, because it is easier to avoid mistakes with:

hdi_series.loc['MEX']

np.float64(0.709)

than it is to work out the position of Mexico in the array of values, and then do:

hdis_array[11] # Was Mexico really at position 11?

np.float64(0.824)

— oh, whoops, we mean:

hdis_array[12] # Ouch, no, it was at position 12.

np.float64(0.709)

As well as being harder to make mistakes, it makes the code easier to read, and therefore, easier to debug.

But the real value from this idea comes when you have more than one Series with corresponding labels.

For example, we can also make a Series with the fertility rate (fert_rate)

data, like this:

# Make a series of the fertility rates

fert_rate_series = pd.Series(fert_rates_array, index=country_codes_array)

fert_rate_series

AUS 1.764

BRA 2.247

CAN 1.510

CHN 1.628

DEU 1.386

ESP 1.210

FRA 1.876

GBR 1.641

IND 3.350

ITA 1.249

JPN 1.346

KOR 1.467

MEX 2.714

RUS 1.190

USA 2.030

dtype: float64

But now imagine we want to look at the corresponding HDI and fert_rate

values. We can do this separately, for each Series, like this:

# Label-based indexing

fert_rate_series.loc['MEX']

np.float64(2.714)

# Label-based indexing

hdi_series.loc['MEX']

np.float64(0.709)

Pandas Data Frames (aka dictionary-like collection of series)#

Imagine though, that we’re going to be doing this for multiple countries, and that we have multiple (not just two) values per country. We would like a way of putting these Series together into something like a table, where the rows have labels (just as the Series values do), and the columns have names.

Each Series corresponds to one column in this table. Pandas calls these tables Data Frames.

# Creating a DataFrame from a dictionary

df = pd.DataFrame({'Human Development Index': hdi_series,

'Fertility Rate': fert_rate_series})

df

| Human Development Index | Fertility Rate | |

|---|---|---|

| AUS | 0.896 | 1.764 |

| BRA | 0.668 | 2.247 |

| CAN | 0.890 | 1.510 |

| CHN | 0.586 | 1.628 |

| DEU | 0.890 | 1.386 |

| ESP | 0.828 | 1.210 |

| FRA | 0.844 | 1.876 |

| GBR | 0.863 | 1.641 |

| IND | 0.490 | 3.350 |

| ITA | 0.842 | 1.249 |

| JPN | 0.883 | 1.346 |

| KOR | 0.824 | 1.467 |

| MEX | 0.709 | 2.714 |

| RUS | 0.733 | 1.190 |

| USA | 0.894 | 2.030 |

Think of the Data Frame as being like a dictionary of Series.

The keys in this dictionary are the column names we provided:

Human Development IndexandFertility Rate.The values are the corresponding Series.

Notice that the Data Frame, like the Series, has an Index:

# The Index of the Data Frame.

df.index

Index(['AUS', 'BRA', 'CAN', 'CHN', 'DEU', 'ESP', 'FRA', 'GBR', 'IND', 'ITA',

'JPN', 'KOR', 'MEX', 'RUS', 'USA'],

dtype='str')

Pandas created the Data Frame Index by looking at the Index of each of the Series from which we built the Data Frame.

In this case, the Series had the same values in their Indices, so the Index for the Data Frame is the same as the Index for the each and both Series:

Exercise 1

Perhaps your agile mind is racing ahead, wondering what Pandas would do if the two Series had different Indices.

As an experiment, imagine now we have another Series that has a slightly

different Index. Let’s say for example, that we have taken the original

fert_rate_series, and sorted it in reverse alphabetical order by Index

value. Here is the Pandas code to do that:

# Sort fert_rate_series in reverse alphabetical order by Code.

fert_rate_reversed = fert_rate_series.sort_index(ascending=False)

fert_rate_reversed

USA 2.030

RUS 1.190

MEX 2.714

KOR 1.467

JPN 1.346

ITA 1.249

IND 3.350

GBR 1.641

FRA 1.876

ESP 1.210

DEU 1.386

CHN 1.628

CAN 1.510

BRA 2.247

AUS 1.764

dtype: float64

Now imagine we create a new Data Frame with the original hdi Series and fert_rate_reversed:

# Creating a new DataFrame from a dictionary, with one Series reversed.

df2 = pd.DataFrame({'Human Development Index': hdi_series,

'Fertility Rate': fert_rate_reversed})

What would you expect to see if you display df2? Have a think, then uncomment the cell below to display the value of df2:

# df2

Why do you think you see this outcome?

To test your theory, consider a new Data Frame where we specify the reversed Series first in the dictionary:

# New DataFrame from a dictionary, reversed Series first.

df3 = pd.DataFrame({'Fertility Rate': fert_rate_reversed,

'Human Development Index': hdi_series})

Yes, the columns will be in the opposite order, Fertility Rate first, then Human Development Index second. But what order will the rows be in (what will the Index order be)?

Reflect, then try running the cell below after removing the # :

# df3

Was your theory right? If not, what is your new theory?

Now consider this:

# New DataFrame from a dictionary, reversed Series first.

hdi_reversed = hdi_series.sort_index(ascending=False)

hdi_reversed

USA 0.894

RUS 0.733

MEX 0.709

KOR 0.824

JPN 0.883

ITA 0.842

IND 0.490

GBR 0.863

FRA 0.844

ESP 0.828

DEU 0.890

CHN 0.586

CAN 0.890

BRA 0.668

AUS 0.896

dtype: float64

df4 = pd.DataFrame({'Fertility Rate': fert_rate_reversed,

'Human Development Index': hdi_reversed})

What does your new theory predict about the new df4? Consider, then have a look.

# df4

Maybe your theory does fit, maybe it does not. If it does not, what is your new theory? To test further, consider what would happen here:

# Scramble the row order a bit.

row_order = [0, 1, 2] + [14, 13, 12, 11, 10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3]

fert_scrambled = fert_rate_series.iloc[row_order]

fert_scrambled

AUS 1.764

BRA 2.247

CAN 1.510

USA 2.030

RUS 1.190

MEX 2.714

KOR 1.467

JPN 1.346

ITA 1.249

IND 3.350

GBR 1.641

FRA 1.876

ESP 1.210

DEU 1.386

CHN 1.628

dtype: float64

df5 = pd.DataFrame({'Fertility Rate': fert_scrambled,

'Human Development Index': hdi_reversed})

# df5

After these examples, what is your final working theory about the algorithm Pandas uses to match the Indices of Series, when creating Data Frames?

Solution to Exercise 1

Here’s our hypothesis of the algorithm:

First check if the Series Indices are the same. If so, use the Index of any Series.

If they are not the same, first sort all Series by their Index values, and use the resulting sorted Index.

What was your hypothesis? If it was different from ours, why do you think yours fits the results better? What tests would you do to test your theory against our theory?

Selecting columns from a Data Frame#

We can get the Human Development Index (hdi) Series by name, by using direct indexing into the Data Frame, like this:

# Getting the Human Development Index series by name

hdi_from_df = df['Human Development Index']

hdi_from_df

AUS 0.896

BRA 0.668

CAN 0.890

CHN 0.586

DEU 0.890

ESP 0.828

FRA 0.844

GBR 0.863

IND 0.490

ITA 0.842

JPN 0.883

KOR 0.824

MEX 0.709

RUS 0.733

USA 0.894

Name: Human Development Index, dtype: float64

Note

Direct and indirect indexing

We use the term direct indexing to mean indexing without going through an

accessor. Direct indexing therefore, is where the opening square bracket

follows the Data Frame or Series value, as in: df['Human Development Index']. There is no accessor method between the Data Frame value df and

the opening square bracket. It is a detail for our purposes, but this means

it is the df.__getitem__ method that handles the indexing request.

By contrast, indirect indexing is where we index into the Data Frame or

Series object via an accessor method such as loc and iloc. In this

case, the square bracket follows the accessor method name, rather than the

object itself. Thus df.iloc[0] (see below) is indirect indexing, using the

iloc accessor. Again, this is a detail, but indirect indexing with e.g.

iloc means it is the (e.g.) df.iloc.__getitem__ method that handles the

indexing request.

In general, in Pandas, the behavior of direct indexing can differ from that of

indirect indexing with .loc or .iloc, particularly direct indexing of Data

Frames. As a general rule, it is wise to prefer indirect indexing with .loc

and .iloc unless you are confident about the behavior of direct indexing.

You’ll notice that we restrict ourselves to using direct indexing on Data Frames (not Series), and when we do use direct indexing, we use it in two specific situations, for which is it very easy to reason about the results:

Selection of columns by column name;

Selection of rows with Boolean Series.

Remember that a Data Frame is a dictionary-like collection of Series.

The Human Development Index column is now a Series contained inside the df

Data Frame.

We have fetched that embedded Series by using direct indexing. We place the

column name ('Human Development Index') between square brackets following

the data frame value, so 'Human Development Index' specified what we want to

select from the Data Frame. We get back a new Series, extracted from the Data Frame:

# Show the type of `hdi_from_df`

type(hdi_from_df)

pandas.Series

What’s in a name?#

You can see in the output display that the extracted Series now has an extra

attribute, which is the name.

# Show the extracted Series again. Notice the Name.

hdi_from_df

AUS 0.896

BRA 0.668

CAN 0.890

CHN 0.586

DEU 0.890

ESP 0.828

FRA 0.844

GBR 0.863

IND 0.490

ITA 0.842

JPN 0.883

KOR 0.824

MEX 0.709

RUS 0.733

USA 0.894

Name: Human Development Index, dtype: float64

We said above that Series are the association between an array of .values,

and a corresponding collection of labels, in .index. Now we see that the

Series also has a .name, that we had not set in our original series:

# The `name` attribute of the Series we've extracted from the Data Frame.

hdi_from_df.name

'Human Development Index'

Above, when we first built the series of HDI values and labels with

pd.Series, we not set the name of the Series, so it got the default .name

of None. We rebuild it here:

# We rebuild with pd.Series.

hdi_series = pd.Series(hdis_array, index=country_codes_array)

# When we don't specify the name, the default is None.

hdi_series.name is None

True

It can be useful to set the .name attribute can be useful for remind you of

the nature of the data in the .values array.

Let’s make a new Series — called hdi_series_named — where we do specify

a .name attribute when calling the pd.Series() constructor.

# Make a series from the `hdis` array, specifying the `name` attribute.

hdi_series_named = pd.Series(hdis_array,

index=country_codes_array,

name='HDI')

# Show the `name` attribute.

hdi_series_named.name

'HDI'

You can set the name on an existing Series using the .name attribute:

hdi_series_named.name = 'Hum Dev Ind'

hdi_series_named

AUS 0.896

BRA 0.668

CAN 0.890

CHN 0.586

DEU 0.890

ESP 0.828

FRA 0.844

GBR 0.863

IND 0.490

ITA 0.842

JPN 0.883

KOR 0.824

MEX 0.709

RUS 0.733

USA 0.894

Name: Hum Dev Ind, dtype: float64

Indirect indexing into Data Frames#

Indirect indexing occurs when we use the .loc and .iloc accessor methods

on the Data Frame, to get rows by label (index value) or by position:

# Using `.loc` indirect indexing on the Data Frame.

df.loc['MEX']

Human Development Index 0.709

Fertility Rate 2.714

Name: MEX, dtype: float64

Notice what Pandas did here. As for .loc indexing into Series, .loc

indexing into the Data Frame with a single label returns the contents of

the row. And Pandas, being a general thinker, sees that the contents of the

row are values, that have labels, where the labels are the column names. Thus

it returns the row to you as a new Series, where the Series has values from

the row values, and labels from the column names.

Indexing with more than one value returns a subset of the Data Frame. In strict parallel to indexing into a Series, indexing with multiple values into a Data Frame, returns a subset of the Data Frame, which is itself, a Data Frame.

# Using `.loc` with index labels

df.loc[['KOR', 'USA']]

| Human Development Index | Fertility Rate | |

|---|---|---|

| KOR | 0.824 | 1.467 |

| USA | 0.894 | 2.030 |

What is a Series? What is a Data Frame?#

A Series is the association of:

An array of values (

.values)A sequence of labels for each value (

.index)A name (which can be

None).

A Data Frame is a dictionary-like collection of Series.

For a Series, the .index has labels corresponding to the values.

For a Data Frame, the .index has labels corresponding the rows.

Adding more columns to the Data Frame#

We have more data to add to our Data Frame. Let’s add those data as new columns, and then compare the result with the Data Frame we get from loading a data file containing the same data.

First, we make another Numpy array, containing the full name of each country.

# Making an array containing the name of each country

country_names_array = np.array(['Australia', 'Brazil', 'Canada',

'China', 'Germany', 'Spain',

'France', 'United Kingdom', 'India',

'Italy', 'Japan', 'South Korea',

'Mexico', 'Russia', 'United States'])

country_names_array

array(['Australia', 'Brazil', 'Canada', 'China', 'Germany', 'Spain',

'France', 'United Kingdom', 'India', 'Italy', 'Japan',

'South Korea', 'Mexico', 'Russia', 'United States'], dtype='<U14')

Now, we get the population of each country, in millions.

# The population of each country in millions, in the year 2000.

population_array = np.array([ 19.1324, 174.0182, 30.8918,

1269.5811, 81.7972, 41.0197,

59.4837, 59.0573, 1057.9227,

57.2722, 127.0278, 46.7666,

98.6255, 146.7177, 281.4841])

population_array

array([ 19.1324, 174.0182, 30.8918, 1269.5811, 81.7972, 41.0197,

59.4837, 59.0573, 1057.9227, 57.2722, 127.0278, 46.7666,

98.6255, 146.7177, 281.4841])

We are about to put a new Series into the Data Frame.

Remember that we can fetch the Series corresponding to a particular column like this:

# Getting the Human Development Index Series by name

hdi_from_df = df['Human Development Index']

hdi_from_df

AUS 0.896

BRA 0.668

CAN 0.890

CHN 0.586

DEU 0.890

ESP 0.828

FRA 0.844

GBR 0.863

IND 0.490

ITA 0.842

JPN 0.883

KOR 0.824

MEX 0.709

RUS 0.733

USA 0.894

Name: Human Development Index, dtype: float64

Here we are indexing (in fact direct indexing) into the Data Frame df, on the right-hand-side (RHS) of the = to fetch the corresponding Series.

We can put data in a new or existing column in the Data Frame by using direct indexing on the left-hand-side of the assignment, like this:

# Add the array as a column in the DataFrame.

df['Population'] = population_array

df

| Human Development Index | Fertility Rate | Population | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AUS | 0.896 | 1.764 | 19.1324 |

| BRA | 0.668 | 2.247 | 174.0182 |

| CAN | 0.890 | 1.510 | 30.8918 |

| CHN | 0.586 | 1.628 | 1269.5811 |

| DEU | 0.890 | 1.386 | 81.7972 |

| ESP | 0.828 | 1.210 | 41.0197 |

| FRA | 0.844 | 1.876 | 59.4837 |

| GBR | 0.863 | 1.641 | 59.0573 |

| IND | 0.490 | 3.350 | 1057.9227 |

| ITA | 0.842 | 1.249 | 57.2722 |

| JPN | 0.883 | 1.346 | 127.0278 |

| KOR | 0.824 | 1.467 | 46.7666 |

| MEX | 0.709 | 2.714 | 98.6255 |

| RUS | 0.733 | 1.190 | 146.7177 |

| USA | 0.894 | 2.030 | 281.4841 |

This assignment says “take the values in population_array and make a new

column (Series) named 'Population' in the Data Frame”.

Remember the maxim that “a Data Frame is just a dictionary-like collection of Series”?

Our new Population column has now become a Series inside the df Data

Frame, where the .values of that Series are the values from population_array.

We can fetch that new 'Population' Series from the Data Frame by direct

indexing, as we did above for the 'Human Development Index' column / Series.

# Fetch Series named 'Population' using direct indexing into the DataFrame.

pop_from_df = df['Population']

pop_from_df

AUS 19.1324

BRA 174.0182

CAN 30.8918

CHN 1269.5811

DEU 81.7972

ESP 41.0197

FRA 59.4837

GBR 59.0573

IND 1057.9227

ITA 57.2722

JPN 127.0278

KOR 46.7666

MEX 98.6255

RUS 146.7177

USA 281.4841

Name: Population, dtype: float64

The .name of the Series is the name of the column from which it was fetched:

# Show the .name attribute of the new Series inside the Data Frame.

pop_from_df.name

'Population'

The values of the new Series are the ones we put in in the assignment above:

# Show the array containing the data for the new Series.

pop_from_df.values

array([ 19.1324, 174.0182, 30.8918, 1269.5811, 81.7972, 41.0197,

59.4837, 59.0573, 1057.9227, 57.2722, 127.0278, 46.7666,

98.6255, 146.7177, 281.4841])

Notice that the extracted pop_from_df Series has an Index, and the Index is

the same as the Index of the Data Frame. In other words, in extracting the

'Population' Series, the Series has inherited the Index from the Data Frame.

We could have used the pd.Series() constructor to build the same Series, built from its components:

# We can build a similar Series to the one we fetched like this.

population_series = pd.Series(population_array,

index=country_codes_array,

name='Population')

population_series

AUS 19.1324

BRA 174.0182

CAN 30.8918

CHN 1269.5811

DEU 81.7972

ESP 41.0197

FRA 59.4837

GBR 59.0573

IND 1057.9227

ITA 57.2722

JPN 127.0278

KOR 46.7666

MEX 98.6255

RUS 146.7177

USA 281.4841

Name: Population, dtype: float64

Let’s use the same df['Name'] = array syntax to add a final column to our Data Frame, containing the full country names:

# Adding in the country names

df['Country Name'] = country_names_array

Here is our full Data Frame - built from its component ingredients - in its resplendent glory:

# View the full DataFrame.

df

| Human Development Index | Fertility Rate | Population | Country Name | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUS | 0.896 | 1.764 | 19.1324 | Australia |

| BRA | 0.668 | 2.247 | 174.0182 | Brazil |

| CAN | 0.890 | 1.510 | 30.8918 | Canada |

| CHN | 0.586 | 1.628 | 1269.5811 | China |

| DEU | 0.890 | 1.386 | 81.7972 | Germany |

| ESP | 0.828 | 1.210 | 41.0197 | Spain |

| FRA | 0.844 | 1.876 | 59.4837 | France |

| GBR | 0.863 | 1.641 | 59.0573 | United Kingdom |

| IND | 0.490 | 3.350 | 1057.9227 | India |

| ITA | 0.842 | 1.249 | 57.2722 | Italy |

| JPN | 0.883 | 1.346 | 127.0278 | Japan |

| KOR | 0.824 | 1.467 | 46.7666 | South Korea |

| MEX | 0.709 | 2.714 | 98.6255 | Mexico |

| RUS | 0.733 | 1.190 | 146.7177 | Russia |

| USA | 0.894 | 2.030 | 281.4841 | United States |

Comparing the built and loaded Data Frames#

This page built a Data Frame from scratch from Numpy components, to deepen our understanding of what a Data Frame is made from.

The cell below shows a more typical method of making a Data Frame, that is

asking Pandas to create a new Data Frame by loading data from a file. We use

the pd.read_csv() function to read some data from a .csv file:

# Import data from a csv file

loaded_df = pd.read_csv("data/year_2000_hdi_fert.csv")

loaded_df

| Code | Human Development Index | Fertility Rate | Population | Country Name | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | AUS | 0.896 | 1.764 | 19.1324 | Australia |

| 1 | BRA | 0.668 | 2.247 | 174.0182 | Brazil |

| 2 | CAN | 0.890 | 1.510 | 30.8918 | Canada |

| 3 | CHN | 0.586 | 1.628 | 1269.5811 | China |

| 4 | DEU | 0.890 | 1.386 | 81.7972 | Germany |

| 5 | ESP | 0.828 | 1.210 | 41.0197 | Spain |

| 6 | FRA | 0.844 | 1.876 | 59.4837 | France |

| 7 | GBR | 0.863 | 1.641 | 59.0573 | United Kingdom |

| 8 | IND | 0.490 | 3.350 | 1057.9227 | India |

| 9 | ITA | 0.842 | 1.249 | 57.2722 | Italy |

| 10 | JPN | 0.883 | 1.346 | 127.0278 | Japan |

| 11 | KOR | 0.824 | 1.467 | 46.7666 | South Korea |

| 12 | MEX | 0.709 | 2.714 | 98.6255 | Mexico |

| 13 | RUS | 0.733 | 1.190 | 146.7177 | Russia |

| 14 | USA | 0.894 | 2.030 | 281.4841 | United States |

You’ll notice that currently, the index of the Data Frame we just loaded is a sequence of numbers. This is the Index that Pandas creates by default, unless you give it some other information on what the Index should be. We’ll look more at this default Index on the next page.

We can use the .set_index() method of the Data Frame to take the column

containing the three-letter country codes and set it to be the row labels of

the Data Frame (the Index). We will look more at Pandas methods in later

pages.

Here we tell .set_index() the column name to use as the .index

in this case we use the

'Code'column, containing the country codes:

# Set the new Data Frame to have values from the "Code" column as labels.

loaded_labeled_df = loaded_df.set_index('Code')

loaded_labeled_df

| Human Development Index | Fertility Rate | Population | Country Name | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code | ||||

| AUS | 0.896 | 1.764 | 19.1324 | Australia |

| BRA | 0.668 | 2.247 | 174.0182 | Brazil |

| CAN | 0.890 | 1.510 | 30.8918 | Canada |

| CHN | 0.586 | 1.628 | 1269.5811 | China |

| DEU | 0.890 | 1.386 | 81.7972 | Germany |

| ESP | 0.828 | 1.210 | 41.0197 | Spain |

| FRA | 0.844 | 1.876 | 59.4837 | France |

| GBR | 0.863 | 1.641 | 59.0573 | United Kingdom |

| IND | 0.490 | 3.350 | 1057.9227 | India |

| ITA | 0.842 | 1.249 | 57.2722 | Italy |

| JPN | 0.883 | 1.346 | 127.0278 | Japan |

| KOR | 0.824 | 1.467 | 46.7666 | South Korea |

| MEX | 0.709 | 2.714 | 98.6255 | Mexico |

| RUS | 0.733 | 1.190 | 146.7177 | Russia |

| USA | 0.894 | 2.030 | 281.4841 | United States |

Let’s compare this loaded Data Frame to the Data Frame we built from Numpy components.

# The Data Frame we built from its component parts.

df

| Human Development Index | Fertility Rate | Population | Country Name | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUS | 0.896 | 1.764 | 19.1324 | Australia |

| BRA | 0.668 | 2.247 | 174.0182 | Brazil |

| CAN | 0.890 | 1.510 | 30.8918 | Canada |

| CHN | 0.586 | 1.628 | 1269.5811 | China |

| DEU | 0.890 | 1.386 | 81.7972 | Germany |

| ESP | 0.828 | 1.210 | 41.0197 | Spain |

| FRA | 0.844 | 1.876 | 59.4837 | France |

| GBR | 0.863 | 1.641 | 59.0573 | United Kingdom |

| IND | 0.490 | 3.350 | 1057.9227 | India |

| ITA | 0.842 | 1.249 | 57.2722 | Italy |

| JPN | 0.883 | 1.346 | 127.0278 | Japan |

| KOR | 0.824 | 1.467 | 46.7666 | South Korea |

| MEX | 0.709 | 2.714 | 98.6255 | Mexico |

| RUS | 0.733 | 1.190 | 146.7177 | Russia |

| USA | 0.894 | 2.030 | 281.4841 | United States |

The loaded_labeled_df Data Frame was built automatically by Pandas, when

loading in a .csv file using pd.read_csv().

We built the df Data Frame from Numpy arrays and strings.

Both Data Frames contain the same data, and the same labels. In fact, we can

use the .equals method of Data Frames to ask Pandas whether it agrees the

Data Frames are equivalent:

df.equals(loaded_labeled_df)

True

They are equivalent.

Exercise 2

In fact the df and loaded_labeled_df data frames are not exactly the same.

If you look very carefully at the notebook output for the two data frames, you

may be able to spot the difference. Pandas .equals does not care about this

difference, but let’s imagine we did. Try to work out how to change the df

Data Frame to give exactly the same display as we see for

loaded_labeled_df.

Solution to Exercise 2

You probably spotted that the loaded_labeled_df displays a name for the Index. You can also see this displaying the .index on its own:

loaded_labeled_df.index

Index(['AUS', 'BRA', 'CAN', 'CHN', 'DEU', 'ESP', 'FRA', 'GBR', 'IND', 'ITA',

'JPN', 'KOR', 'MEX', 'RUS', 'USA'],

dtype='str', name='Code')

compared to:

df.index

Index(['AUS', 'BRA', 'CAN', 'CHN', 'DEU', 'ESP', 'FRA', 'GBR', 'IND', 'ITA',

'JPN', 'KOR', 'MEX', 'RUS', 'USA'],

dtype='str')

We see that the .name attribute differs for the two Indices; to make the Data Frame displays match, we should set the .name on the df Data Frame.

The simplest way to do that is:

# Make a copy of the `df` Data Frame. This step is unnecessary to solving

# the problem, it is just to be neat.

df_copy = df.copy()

# Set the Index name.

df_copy.index.name = 'Code'

df_copy

| Human Development Index | Fertility Rate | Population | Country Name | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code | ||||

| AUS | 0.896 | 1.764 | 19.1324 | Australia |

| BRA | 0.668 | 2.247 | 174.0182 | Brazil |

| CAN | 0.890 | 1.510 | 30.8918 | Canada |

| CHN | 0.586 | 1.628 | 1269.5811 | China |

| DEU | 0.890 | 1.386 | 81.7972 | Germany |

| ESP | 0.828 | 1.210 | 41.0197 | Spain |

| FRA | 0.844 | 1.876 | 59.4837 | France |

| GBR | 0.863 | 1.641 | 59.0573 | United Kingdom |

| IND | 0.490 | 3.350 | 1057.9227 | India |

| ITA | 0.842 | 1.249 | 57.2722 | Italy |

| JPN | 0.883 | 1.346 | 127.0278 | Japan |

| KOR | 0.824 | 1.467 | 46.7666 | South Korea |

| MEX | 0.709 | 2.714 | 98.6255 | Mexico |

| RUS | 0.733 | 1.190 | 146.7177 | Russia |

| USA | 0.894 | 2.030 | 281.4841 | United States |

Convenient Plotting with Data Frames#

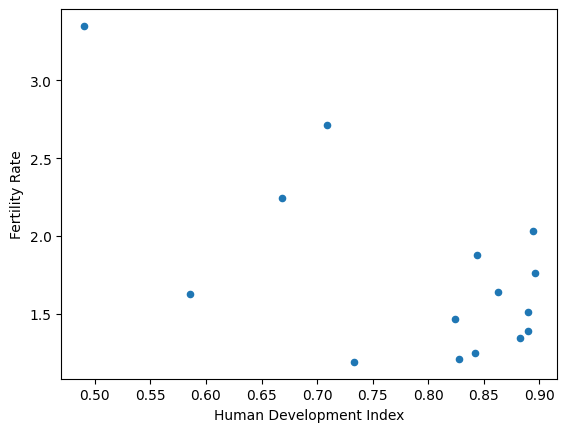

Remember earlier we imported Matplotlib to plot some of our data?

Now we have a Data Frame, we can use the Data Frame’s in-built plotting

machinery, to make the same graph. To do this, we can use the .plot()

method of the Data Frame, and specify the name of a column to plot on the x

axis, and a name of a column to plot on the y axis. We use the kind=

argument to tell Pandas what type of plot we want (in this case a scatter

plot).

# Plotting with Pandas methods.

df.plot(x='Human Development Index',

y='Fertility Rate',

kind='scatter');

In fact the Pandas .plot methods wrap Matplotlib, so the output from using

Matplotlib directly (see towards the top of this page) will look very similar

to the output from using Pandas .plot, but Pandas can, among other things, use column names to make better default axis labels.